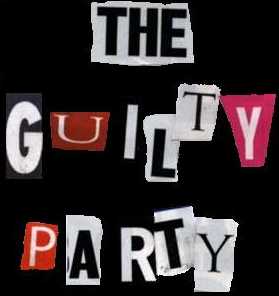

Sona MedSpa Guilty of Negligent Misrepresentation: Forced to cough up $400K

Sona Medspa Guilty of Negligent Misrepresentaion: Franchisee Awarded $400,000

Kempton and Rosita Coady had entered into a Boston-area Development Agreement and a Burlington Franchise Agreement in September 2003, to operate franchise laser hair removal centers. The Coadys had conducted an independent investigation of the business and had consulted with their financial and legal advisors before signing agreements. Kemp Coady testified that they had made their decision based on the information Sona representatives had given them regarding their hair removal technology. But approximately eighteen months into the system, the Coadys felt the "efficacy information" procedure, a much touted Sona method of hair removal, was flawed and constituted negligent misrepresentation under Tennessee law.

Kempton and Rosita Coady had entered into a Boston-area Development Agreement and a Burlington Franchise Agreement in September 2003, to operate franchise laser hair removal centers. The Coadys had conducted an independent investigation of the business and had consulted with their financial and legal advisors before signing agreements. Kemp Coady testified that they had made their decision based on the information Sona representatives had given them regarding their hair removal technology. But approximately eighteen months into the system, the Coadys felt the "efficacy information" procedure, a much touted Sona method of hair removal, was flawed and constituted negligent misrepresentation under Tennessee law.

The Coadys were seeking damages worth approximately $9 million on eleven counts, namely for common law fraud and negligent misrepresentation (Counts 1 and 2). Although the arbitrator did not find the respondents liable for fraud, he did rule guilty on the charge of negligent misrepresentation. But he severely adjusted down the award to approximately $400,000, which only addressed the damages the Coady's claimed through October 2006. The arbitrator's decision of a lower compensation seemed to be influenced by the plaintiff's high education level, their income producing capabilities and an already existing new store that the husband and wife team started, Viva Skin Care Center. Compensation for loss of livelihood was minimized. The Coadys will be required to pay arbitration and legal fees.

Franchisee States, "We Were Very Much Deceived."

At the time of arbitration, Kemp Coady said Sona had a total of 45 franchises in the system, but by November 2006 sixteen franchisees had gone bankrupt or had been transferred to other people. He said, "Most franchisees got in trouble after one to two years of running their centers. Basically they come unwound. The business just stops working."

Coady and his wife are past executives with MBAs from Cornell University. He said that when they invested heavily in the Sona system and the Sona promise they felt they had been deceived, both in terms of its medical premise and, although it was not found in their favor in the decision, in terms of its business model as well. He said, "We were very much deceived."

Coady said, "They negligently misrepresented the medical facts because they did not hire the proper experts to prove what they were telling franchisees was true."

He feels the arbitrator made a good decision in vacating all of the Sona MedSpa and Carousel counter-claims against them. He said, "Now we are independent of Sona, but we still have to try to make our Viva Skin Care Center succeed. That's a tall order with all the baggage we were left with because of Sona.

Sona Replies, "Sona does indeed view the outcome as favorable..."

Read the entire article on Sona medspas from bluemaumau.com.

The lawyer for the Sona franchisee adds this in the comments:

"Look at it in perspective: We prevailed on negligent misrepresentation and recovered money. Sona, which had counterclaims against the Coadys originally in the range of $7 million dollars, (later trimmed down to somewhere between $1 and $2 million dollars) recovered nothing. On my scorecard, that’s a win for my team and a goose egg for the other side. You don’t say that the team that wins the game by one run was the losing team. It was the winner, and win we did.

Now to the meat of the holding: The Claimants were originally induced to buy a Sona franchise in September 2003 on the basis of representations by the then-owner, Dennis Jones, that the Sona hair removal system was far superior to other systems; that it would remove 93 to 98 percent of a person’s unwanted hair in five treatments; that the removal was permanent; that the reason it worked was because of a unique, patent-pending “Sona Concept” that timed the laser treatments to hair growth cycles; and that it had a proprietary chemical, Meladine, that enabled the laser to work on all types of hair when, in fact, lasers typically cannot remove white, blonde, or gray hair. The problem? None of this was true or supported by any credible medical studies. Jones, however, told prospects that he had a database of 50,000 clients verifying the claims.

Coady purchased his franchise on the basis of these representations in September 2003 and proceeded to build out his facility through the ensuing year. In the interim, Carousel, Amos and Rose purchased Sona. One might think that an investment capital firm buying a company engaged in laser hair removal might have retained a dermatologist to evaluate the efficacy of its procedures or that it might have taken note of the mountains of data that said, in substance, that laser hair removal was a hit or miss proposition, that any sort of guarantees were suspect and that overreaching in selling to the public was not unusual. But Carousel, Amos and Rose did none of this. A couple of months after they purchased the company, and while the Coadys were still building out their center, other franchisees, who had been in business for a few months or up to a year, came to Rose with the news that indeed the “Sona Concept” didn’t work: Five treatments were insufficient to remove anywhere near 93 percent of the hair; it wasn’t permanent; and Meladine didn’t work to enable laser treatment of light-colored hair. As a result, customers were complaining they had been misled and were demanding free treatments or refunds. Rose, Amos and Carousel sat on this information through the Summer of 2004 without notifying existing franchisees that they were operating on the basis of bad information, telling their clients falsehoods, or correcting the bad information. When the Coadys went to training at Sona headquarters, in September, they were trained to tell prospective clients all of the same “faulty” information. The Coadys opened their center and repeated those statements to their customers. It was only a year later, when franchisees discovered the full impact of Sona’s falsehoods, and the Coadys learned from a dermatologist that there was no substance to the “Sona Concept,” that they took steps to leave the system.

What is important about the Arbitrator’s ruling is that it found the buyers—Carousel, Amos, Rose and partners of Carousel Capital—guilty of negligent misrepresentation. In short, they knew franchisees had been given bad information, and they sat on their hands and did nothing and allowed it to be repeated to the franchisees’ clients.

An important point that everyone seems to have missed, or misinterpreted, is that it is the very finding of guilt on negligent misrepresentation that makes this an important case. Negligent misrepresentation is a low threshold: It is easy to breach if you are not careful. Hence, the decision casts a very wide net: Purchasers of and investors in franchisors have a duty not to be negligent; they owe a duty of reasonable care to the existing franchisees that they acquire. I repeat: This is a broad standard of care that can be met by reasonable due diligence but also can be very easily breached by a failure to use reasonable due diligence.

There are a number of other chapters of the Sona saga that are worth mentioning here, if only briefly.

In January 2006, the Washington franchisee, also disillusioned with the falsehoods he had been told, de-identified and went independent. Sona sued him in Federal Court seeking a preliminary injunction against violation of his covenant not to compete. Following a two-day hearing, the federal judge in Virginia denied Sona’s request for a preliminary injunction, finding, among other things, that the evidence that Sona’s methods were misleading was sufficient to show a likelihood that the franchisee would be entitled to rescind on the basis of fraud. In the wake of that franchisee’s departure from the system, several others also left.

There was also collateral damage. Sona franchisees did not discover the faulty nature of the system until they had been in business for a year or more and clients had run through the five treatment cycle and found that their hair was still there. At that point, customers began to demand refunds. Also, because of Sona’s quirky cash-based accounting system, franchisees began running out of money about that time. One store, in Salt Lake City, closed its doors, and the franchisee was the subject of action by the Consumer Affairs Department requiring a payment of tens of thousands of dollars in restitution to clients who had not had all their hair removed. A similar case happened in St. Louis. Stories abound of franchisees who lost not only their personal fortunes but also their mental health, their family relations, and their homes. Sona, itself, got off lightly. The point, however, has been made: Those who buy franchised organizations cannot ignore the history that went before. They have a duty to franchisees to make sure they are telling the truth and acting fairly."

--

W. Michael Garner, attorney for the Sona franchisees, is a partner in Dady & Garner, P.A., Minneapolis and New York. The firm represents franchisees, dealers and distributors in their disputes with franchisors and suppliers. Mr. Garner is the author of a three-volume treatise on franchise law, the editor of the Franchise Desk Book, and former editor of the American Bar Association's Franchise Law Journal. He has been practicing franchise and distribution law for over 30 years.

The entire threads worth reading.