Pathogenisis Of Acne

/A brief review of the pathogenesis of acne will create the context for a discussion of the features of the disease in adults and the treatment approaches that target specific pathogenic factors.

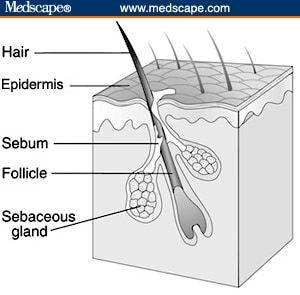

The pilosebaceous unit (the sebaceous follicle,

sebaceous glands, and sebaceous ducts) is the site of acne.

Pilosebaceous units are concentrated in body sites that are prone to

acne

Figure 1. The pilosebaceous unit. (Courtesy NIH)

Excessive sebum production secondary to androgen stimulation.

The differentiation of the sebaceous epithelial cell (the sebocyte) and

the production of sebum are mainly under the control of androgen

hormones. During the prepubertal period, the increase in

adrenal androgens triggers the enlargement of the sebaceous glands,

with a consequent increase in sebum production. With the onset of

puberty and the increase in androgen from the gonads, sebaceous glands

become even more active. In acne patients, the number of

lobules in the sebaceous gland and the size of the sebaceous follicle

are increased compared with people without acne, as is the amount of sebum produced.

However, the components of sebum, which include squalene, wax esters,

triglycerides, cholesterol, and cholesterol esters, do not differ

between people with and without the disease. Excess sebum

production in people with acne is likely caused by differences in

end-organ (pilosebaceous unit) responsiveness to androgens and,

possibly, by increased circulating androgens.

Altered follicular keratinization and desquamation, resulting in follicular plugging. Sebum flows through the canal of the sebaceous follicle, which is lined with a keratinizing epithelium. In acne patients, there is increased production of the corneocytes lining the follicle and retention of these corneocytes within the follicle. The abnormally desquamated corneocytes and the excess sebum build up within the follicle to form a microscopic, bulging mass called the microcomedo. The trigger for corneocyte hyperproliferation is unknown, but androgen stimulation, decreased levels of follicular linoleic acid, increased levels of DHEAS, and interleukin (IL)-1 alpha activity have all been proposed as possible mechanisms.[6]

Proliferation of Propionibacterium acnes, an anaerobic organism normally resident in the follicle. The enclosed, sebum-rich environment of the sebaceous follicle is ideal for the proliferation of P acnes,

the anaerobic bacterium that produces chemotactic factors and recruits

proinflammatory molecules involved in the inflammatory phase of acne. P acnes counts have been shown to be higher in young people (age 16-21) with acne compared with nonacne controls, but no difference in P acnes counts was seen in people aged 21-25 with and without acne.

No differences are apparent in the cutaneous and follicular microflora

of adolescent acne patients, persistent acne patients, and late-onset

acne patients. There is no correlation between acne severity and skin-surface P acnes colonization, but even so, agents that reduce P acnes counts are clinically effective in the treatment of acne.

Inflammation following chemotaxis and the release of proinflammatory mediators. The proliferation of P acnes results in a variety of proinflammatory stimuli, including cytokines such as IL-1, IL-8, IL-12, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and proinflammatory byproducts including proteases, lipases, and chemotactic factors for neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages. Follicular rupture and leakage of lipids, corneocytes, and bacteria into the dermis further exacerbate inflammation.

There

is also evidence, primarily from twin studies, that acne may be

inherited. One study of 204 patients over the age of 25 found that

familial factors were important in determining individual

susceptibility to adult persistent facial acne. The risk

of adult acne occurring in a relative of a patient with adult acne was

nearly 4 times greater than for a relative of an unaffected individual.